Forster, Roger T., and V. Paul Marston. God’s Strategy in Human History. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Bethany House Publishers, 1974. 270.

Calvinistic interpreters understand this entire section to refer to God’s unconditional election and irresistible grace for individual people (vv.17-23). Other Calvinists go further, arguing that this refers to double predestination. Is this the case?

This is not the case. Paul is teaching that God will harden people’s hearts, so that he can get others to receive Christ. But even those who are hardened can turn back to God if they repent. Consider a number of observations that support this interpretation:

First, Pharaoh originally hardened his own heart. God predicted that Pharaoh would harden his heart (Ex. 4:21; 7:3), but Pharaoh was the one who originally did the hardening in Exodus 7:13 through 9:11. God’s first act of hardening Pharaoh was in Exodus 9:12.

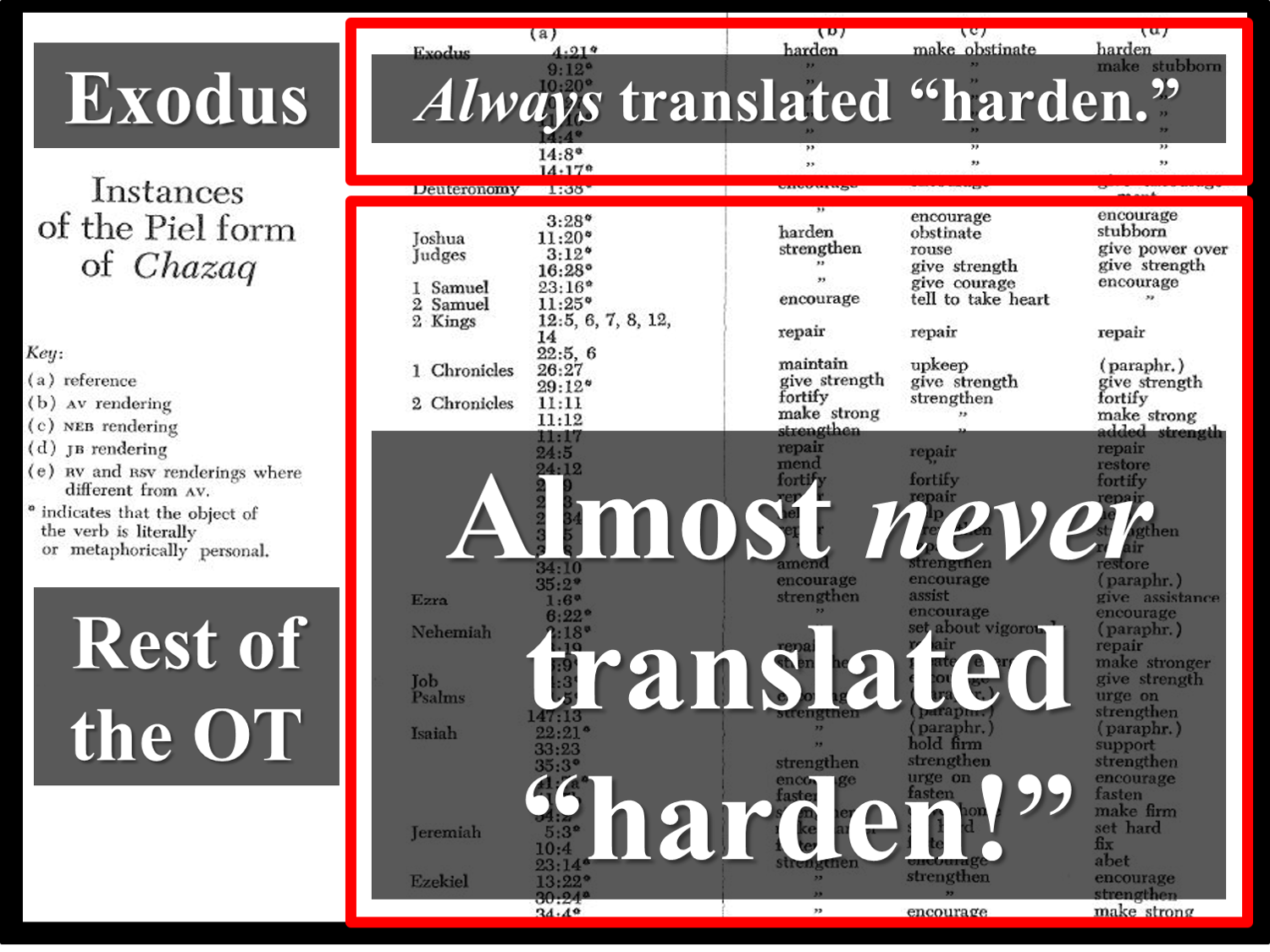

Second, the word “harden” should be translated “strengthen.” The Hebrew word for “harden” (chazaq) can be translated “become strong… encourage… repair.” HALOT defines the word as “be strong, grow strong… prevail over… have courage… harden… gird… repair… sustain.” Forster and Marston show that the term is always translated “harden” in Exodus, but not translated this way in the rest of the OT:

Third, therefore, God gave Pharaoh the “courage” or “strengthening” to carry out his evil desire. Forster and Marston write, “The wicked desire was already in Pharaoh; the Lord’s action simply gave him courage to carry it out… When any normal person would have given in because of fear, Pharaoh received supernatural strength to continue with his evil path of rebellion.” To illustrate this, consider a man who desires to kill his boss, but he doesn’t have the courage to follow through with the murder. To gain the courage, he reaches for a whiskey bottle, so that this “liquid courage” can give him the ability to carry out the thing that he wants to do. In the same way, God gave Pharaoh the strength to do what he had set his mind on doing.

Fourth, hardening people who are totally depraved does not make sense under a Calvinistic view. Calvinists argue that the reprobate are “dead,” which means that they are incapable of even exercising faith in the gospel. But why would God “harden” a person who was spiritually dead from birth? This would be similar to putting a blindfold over a dead corpse.

Fifth, Pharaoh’s individual “hardening” illustrates God’s hardening for the nation of Israel. Pharaoh’s hardening was not capricious on God’s part. Since Pharaoh had rejected God’s word and works, God hardened him (“strengthened him”) to carry out his desire. Therefore, Pharaoh is the archetype for what Paul means when he writes that the nation of Israel had become hardened. This is not referring to arbitrary, unconditional election. Instead, the nation had hardened itself to Jesus’ words and works, and God hardened them (“strengthened them”) to carry out their desire.

Incidentally, this view fits perfectly with what we read in Acts 28. Paul lectured about the gospel all day to some Jewish listeners (Acts 28:23). Luke records that “some were being persuaded by the things spoken, but others would not believe” (v.24). Citing Isaiah 6:9-11, Paul argues that the reason why they don’t believe is because they will not understand and will not perceive (v.26). Specifically, we read, “The heart of this people has become dull, and with their ears they can scarcely hear, and they have closed their eyes” (v.27). However, if they hadn’t turned away from God, Paul states, “They might see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart and return, and I would heal them” (v.27). As a consequence, Paul says that he will take the message to the Gentiles, because “they will also listen” (v.28).

Sixth, the hardening of Israel is neither arbitrary nor fatalistic. The purpose of Israel’s hardening was due to the fact that they were seeking to find salvation through works—not faith (Rom. 9:30-33; 10:3-4), and God was using this hardening to reach innumerable Gentile people. Moreover, Paul writes that individual Israelites are not doomed to unbelief, but can still come to Christ. Paul writes, “They [Israel] did not stumble so as to fall, did they? May it never be! But by their transgression salvation has come to the Gentiles, to make them jealous. Now if their transgression is riches for the world and their failure is riches for the Gentiles, how much more will their fulfillment be!” (Rom. 11:11-12). This passage explicitly teaches that God was using this hardening to reach many Gentiles (“By their transgression salvation has come to the Gentiles”), and there is still hope for individual Israelites (“They did not stumble so as to fall, did they? …How much more will their fulfillment be!”).

Similarly, God’s purpose in hardening Pharaoh was to reach a multitude of people through Pharaoh’s hardening—namely, Israel and beyond. Paul writes, “For this very purpose I raised you up, to demonstrate my power in you, and that my name might be proclaimed throughout the whole Earth” (Rom. 9:17). In Romans 11, Paul turns this around on his Jewish objector. Paul states that God “hardened” the Israelites, so that he could show mercy on the Gentiles (Rom. 11:6-11). At the end of chapter 11, Paul writes, “For God has imprisoned all people in their own disobedience so he could have mercy on everyone” (Rom. 11:32 NLT). The purpose of God’s plan is to show mercy on everyone (“the whole Earth” Rom. 9:17). Earlier, Paul addressed the judgment of God over both ethnic groups: the Gentiles (Rom. 1:18-2:16) and the Jews (Rom. 2:17-3:20). Walls and Dongell write, “If we accept Paul’s strategy of indicting every individual through indictment of the group, then consistency requires that we allow the same extension to hold with regard to God’s mercy, as Romans 11:32 seems to say.”

The scandal of Romans 9 is not that God is choosing to save one person, rather than another. The scandal is that God bringing large numbers of Gentiles into his kingdom, rather than the Jews. While some interpreters read Romans 9 as narrowing God’s plan of salvation, we should read this passage as broadening God’s plan of salvation. For more context, see our earlier article (Romans 9: An Arminian Interpretation).

Forster, Roger T., and V. Paul Marston. God’s Strategy in Human History. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Bethany House Publishers, 1974. 270.

Koehler, L., Baumgartner, W., Richardson, M. E. J., & Stamm, J. J. (1994–2000). The Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 302). Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Forster, Roger T., and V. Paul Marston. God’s Strategy in Human History. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Bethany House Publishers, 1974. 65, 66.

Leighton Flowers, The Potter’s Promise: A Biblical Defense of Traditional Soteriology (Trinity Academic Press, 2017), 50.

Jerry Walls and Joseph Dongell, Why I Am not a Calvinist (Downers Grove, IL, InterVarsity, 2004), 51.

James earned a Master’s degree in Theological Studies from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, graduating magna cum laude. He is the founder of Evidence Unseen and the author of several books. James enjoys serving as a pastor at Dwell Community Church in Columbus, Ohio, where he lives with his wife and their two sons.