Geisler, Norman & Nix, William. A General Introduction to the Bible: Revised and Expanded. Chicago, IL. Moody Press. 1986. 271.

The term “Apocrypha” comes from a Greek term which means “hidden away.” When referring to the many books included, we call these the Apocrypha (plural), rather than Apocryphon (singular).

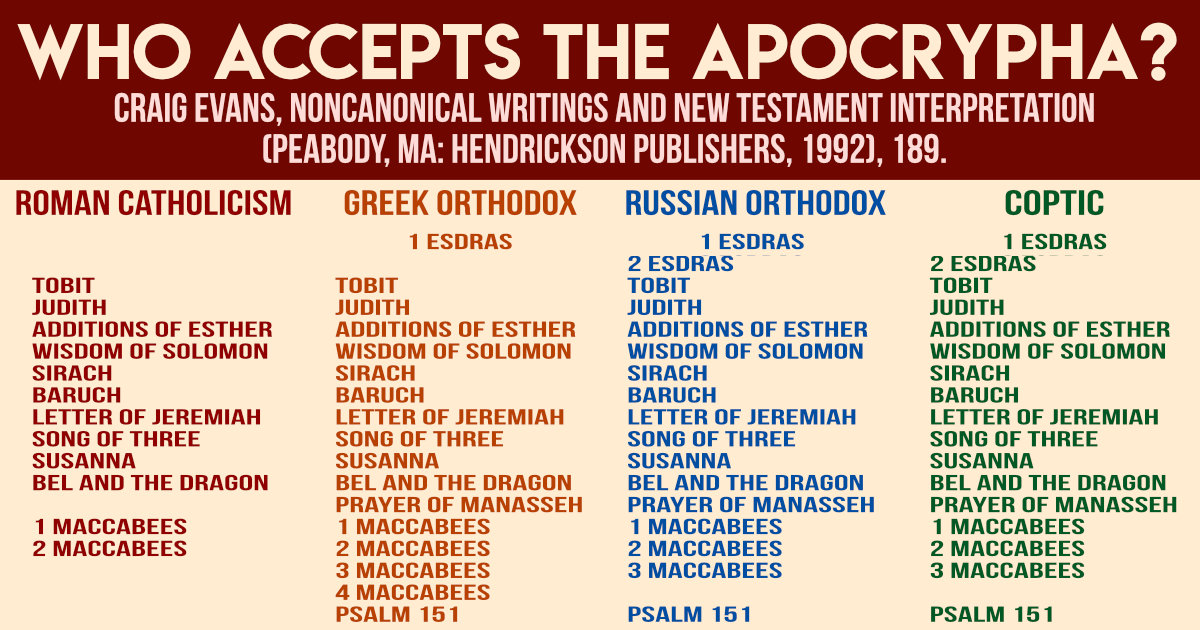

Protestants reject all of the Apocrypha, while Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, and Coptic Christians accept some of them.

Who accepts the Apocrypha and which books do they accept? Chart generously taken from Craig Evans, Noncanonical Writings and New Testament Interpretation (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1992), p.189. | ||||

Apocrypha | Roman Catholic | Greek Orthodox | Russian Orthodox | Coptic |

1 Esdras | 1 Esdras | 1 Esdras | ||

2 Esdras | 2 Esdras | |||

Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit | Tobit |

Judith | Judith | Judith | Judith | Judith |

Additions of Esther | Additions of Esther | Additions of Esther | Additions of Esther | Additions of Esther |

Wisdom of Solomon | Wisdom of Solomon | Wisdom of Solomon | Wisdom of Solomon | Wisdom of Solomon |

Sirach | Sirach | Sirach | Sirach | Sirach |

Baruch | Baruch | Baruch | Baruch | Baruch |

Letter of Jeremiah | Letter of Jeremiah | Letter of Jeremiah | Letter of Jeremiah | Letter of Jeremiah |

Song of Three | Song of Three | Song of Three | Song of Three | Song of Three |

Susanna | Susanna | Susanna | Susanna | Susanna |

Bel and the Dragon | Bel and the Dragon | Bel and the Dragon | Bel and the Dragon | Bel and the Dragon |

Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh | |

1 Maccabees | 1 Maccabees | 1 Maccabees | 1 Maccabees | 1 Maccabees |

2 Maccabees | 2 Maccabees | 2 Maccabees | 2 Maccabees | 2 Maccabees |

3 Maccabees | 3 Maccabees | 3 Maccabees | ||

4 Maccabees | 4 Maccabees | |||

Psalm 151 | Psalm 151 | Psalm 151 | ||

Those who accept the Apocrypha choose to call these books the Deuterocanonical Scriptures (literally “second” “canon”). To them, this doesn’t mean that the Apocrypha are secondarily inspired—anymore than Deuteronomy (literally “second” “law”) is less inspired than Exodus.

Evangelical Christians reject the Apocrypha. As we have already argued, the apocryphal books should not be held to be Scripture, because they were not written by a prophet (see “The OT Canon”). In fact, there is good evidence that the apocryphal books should be rejected.

Several lines of evidence point toward the rejection of the Apocrypha by the Jewish community. This is interesting because the NT affirms that the Jewish community knew that their Scriptures were inspired—at least by the first-century AD. Paul writes that the Jewish people “were entrusted with the oracles of God” (Rom. 3:2). Jesus spoke to the Sadducees of “what was spoken to you by God” (Mt. 22:31; cf. Jn. 5:39; Acts 17:2, 11; 28:23). How could the NT authors make such statements if the Jewish people didn’t know their own Scriptures? Why do we never find the NT authors disputing with the Jewish people over which books were inspired?

These passages directly imply that the Jewish people knew their own canon. What then did the Jewish people believe about their own Scriptures?

First, the Apocrypha never claim to be inspired. Geisler and Nix write, “There is no claim within the Apocrypha that it is the Word of God. It is sometimes asserted that Ecclesiasticus 50:27–29 lays claim to divine inspiration, but a closer examination of the passage indicates that it is illumination and not inspiration that the author claims to have.” Beckwith argues that Ecclesiasticus is simply referring to the Pentateuch as the basis for its source of “prophecy.”

Second, Apocrypha reject their own prophetic origin. 1 Maccabees repeatedly states that prophets did not exist during its time:

(1 Maccabees 4:46) “And they laid up the stones in the mountain of the temple in a convenient place, till there should come a prophet, and give answer concerning them.”

(1 Maccabees 9:27) “And there was a great tribulation in Israel, such as was not since the day, that there was no prophet seen in Israel.”

(1 Maccabees 14:41) “And that the Jews, and their priests, had consented that he should be their prince, and high priest forever, till there should arise a faithful prophet.”

Third, the DSS rejected the Apocrypha (~150 BC). Scholar R. Laird Harris writes, “Apocryphal and pseudepigraphal literature is found and is referred to, but is never quoted as authoritative. Jubilees is mentioned by name in the Zadokite Document, but not with any formula that would designate it as authoritative.”

Fourth, the Book of Jubilees rejects the Apocrypha (2nd century BC). This book is generally dated to the second century BC, and we know this because the Essenes at Qumran used it. We only possess the book in fragments, but John of Constantinople and Georgius Syncellus both cite the work as reflecting a 22 book canon.

Fifth, Philo never quoted from the Apocrypha (20 BC-AD 40). Philo lived in Alexandria, where the Septuagint was originally translated. While Philo quoted from the OT over two thousand times, he “never once quotes an uncanonical Jewish book.”

Sixth, Josephus rejected the Apocrypha (AD 75-99). The Roman general Titus had given Josephus a gift of the complete OT scrolls (Josephus, The Life, 75; 418). Therefore, he is an especially credible witness on the Hebrew canon because he had the actual Temple scrolls in his possession. He writes in Against Apion:

For we have not an innumerable multitude of books among us, disagreeing from and contradicting one another (as the Greeks have), but only twenty-two books, which contain the records of all the past times; which are justly believed to be divine; and of them, five belong to Moses, which contain his laws, and the traditions of the origin of mankind until his death. This interval of time is little short of three thousand years; but as to the time from the death of Moses till the reign of Artexerxes king of Persia, who reigned after Xerxes, the prophets, who were after Moses, wrote down what was done in their times in thirteen books. The remaining four books contain hymns to God, and precepts for the conduct of human life. From Artexerxes to our own time the complete history has been written but has not been deemed worthy of equal credit with the earlier records because of the failure of the exact succession of the prophets. We have given practical proof of our reverence for our own scriptures. For, although such long ages have now passed, no one has ventured to add, or to remove, or to alter anything, and it is an instinct with every Jew, from the day of his birth, to regard them as decrees of God…” (Against Apion, 1:8)

Scholar David deSilva writes, “The evidence from Josephus is also striking: while he knows 1 Esdras and 1 Maccabees, he lists a canon similar to that embraced in Palestine at the same time.”

Seventh, Aquila rejected the Apocrypha (AD 135). According to Jerome (Commentary on Isaiah, on 8:11ff), Aquila was a Jewish proselyte and a pupil of Rabbi Akiba. Epiphanius claims that Aquila made a literal translation of the Hebrew Scriptures around AD 128 (De Mensuris et Ponderibus, 113-16). In the surviving fragments, there is “no hint of it including any apocryphal book” and it “included all five of the disputed books.” He cites Esther in Greek which is found in a midrash of Esther (Rabbah 2.7). Beckwith claims that Aquila’s “rabbinical credentials are unimpeachable.”

Eighth, we do not have a single source reflecting a Jewish dispute over the Apocrypha. Beckwith writes, “The absence of disputes about the Apocrypha (or… the Pseudepigrapha) in the rabbinical literature is an eloquent fact… Yet not a trace of such events has been left in all the voluminous records of rabbinical tradition, and it is hard to resist the inference that no such events can possibly have occurred.”

Jesus and the apostles are never once found arguing with their theological opponents over which books should belong in the Bible. Instead, they assume that the Jewish people knew which books were inspired (Rom. 3:2; Mt. 22:29-31). Jesus said, “The blood of all the prophets, shed since the foundation of the world, may be charged against this generation, from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who was killed between the altar and the house of God” (Lk. 11:49-50). Abel dates to the beginning of the biblical record (Gen. 4), and Zechariah dates to the end (2 Chron. 24).

The NT authors quote or allude to the OT roughly 600 times. They often say, “The Scriptures say…” or “As it is written…” or “Thus says the Lord…” But they never once cite an Apocryphal book in this way. Even Catholic apologist Dave Armstrong admits, “The New Testament does not quote any of these books directly.”

In the King James Bible, the New Testament contains 181,253 words. Likewise, the Apocrypha contain 152,185 words. The Apocrypha contain a voluminous amount of literature, and yet, the NT never cites these books as authoritative Scripture.

Catholic theologians often retort that the NT authors do allude to the Apocryphal books. This may be true. However, this doesn’t weaken the force of the argument. After all, the NT authors quote non-Christian and pseudepigraphal literature. Paul quoted Pagan poets and philosophers like Cleanthes, Aratus, and Menander (Acts 17:28; 1 Cor. 15:33). He likewise affirmed the statement of Epimenides, writing that his “testimony is true” (Titus 1:12-13). Jude cites from both the pseudepigraphal Assumption of Moses (Jude 9) and the Book of Enoch (Jude 14-15). Allusions to these books do not make them inspired (as Catholic theologians would surely agree). Atheistic historians appeal to 1 Maccabees on its historical grounds, but they do not cite these books as inspired texts!

Therefore, the point still stands: If the NT authors believed in the inspiration of the Apocrypha, why don’t they quote these books as inspired Scripture?

Comparative Size of the Apocrypha | |||

| Chapters | Verses | Words |

Old Testament | 929 | 23,214 | 592,439 |

New Testament | 260 | 7,959 | 181,253 |

Apocrypha | 183 | 6,081 | 152,185 |

Melito (bishop of Sardis, AD 170). Melito travelled to Palestine to discover “an accurate statement of the ancient books, as regards their number and their order.” Melito writes,

Accordingly when I went to the East and reached the place where these things were preached and done, I learned accurately the books of the Old Testament, and I send them to you as written below. These are their names: Of Moses five, Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Leviticus, Deuteronomy; Joshua the son of Nun, Judges, Ruth, four of Kingdoms, two of Chronicles, the Psalms of David, Solomon’s Proverbs or Wisdom, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Job; of the Prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, the Twelve [minor prophets] in one book, Daniel, Ezekiel, Ezra. From which also I have made the extracts, dividing them into six books.

In short, Melito held the same Hebrew canon that we have today—minus the book of Esther.

Origen (AD 250). Origen stated that there were 22 books in the OT canon. Origen did however “included the apocryphal Letter of Jeremiah in his Old Testament canon.” Origen’s disciples (e.g. Cyril of Jerusalem, Athanasius, Hilary of Poitiers, Gregory of Nazianus, Rufinas”) “all have a 22-book Old Testament like the one Origen had attributed to the Jews.”

Eusebius (AD 317). He agrees with Josephus that the OT only contains 22 books, and no books were added after the time of Artaxerxes (Ecclesiastical History, 3.10.1-5).

Cyril of Jerusalem (AD 350). He wrote, “Read the divine Scriptures, these twenty-two books of the Old Testament… Read their twenty-two books but have nothing to do with the apocryphal writings.”

Hilary of Poitiers (AD 367). He published “a canon of the Old Testament in the prologue to his commentary on the Psalms. It consists of the twenty-two books of the Hebrew Bible and of our present Old Testament.”

Athanasius (Bishop of Alexandria, AD 367). Athanasius listed all of the books in our Bible (minus Esther). He writes, “There are other books besides these not indeed included in the Canon, but appointed by the Fathers to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness. The Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Sirach, and Esther, and Judith, and Tobit, and that which is called the Teaching of the Apostles, and the Shepherd. But the former, my brethren, are included in the Canon, the latter being [merely] read; nor is there in any place a mention of apocryphal writings. But they are an invention of heretics, who write them when they choose, bestowing upon them their approbation, and assigning to them a date, that so, using them as ancient writings, they may find occasion to lead astray the simple” (Athanasius, Paschal Letter Letter 39). Historian Gregg Allison does note that Athanasius did, however, include “the Letter of Jeremiah and Baruch in his canonical list.”

Epiphanius (AD 368). He was a disciple of Athanasius, who also “endorsed a canon limited to the twenty-two books of the Hebrew Bible.” In his first list (Panorion, 1.1.8.6), Epiphanius includes the epistle of Jeremiah and 1 Esdras (and in one manuscript, he adds Judith and Tobit to Esther). However, Beckwith writes, “By the time that he wrote De Mensuris et Ponderibus… Epiphanius seems to have known better… The contents of the lists appear to be exactly identical to the contents of Jerome’s.”

Rufinus (AD 390). He affirms the twenty-two book canon.

Jerome (AD 400). Jerome studied under a Jewish rabbi in Palestine, and he was a Hebrew scholar. He firmly believed that there were only 22 books in the OT. He writes, “As then the church reads Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees, but does not admit them among the canonical Scriptures, so let it read these two volumes for the edification of the people, not to give authority to doctrines of the church.”

Pope Damascus commissioned Jerome to translate the Apocrypha into Latin in AD 383. Jerome translated 12 apocryphal books with protest, worrying that people would think these were Scripture. Unfortunately, his concerns came to fruition. While Jerome did translate Judith and Tobit, Harris writes, “He did [this] very hastily, apparently, without great respect for them,” and he “expressly ruled the Apocryphal books out of the canon.”

Gregory the Great (Roman Catholic pope, sixth century AD). He writes, “With reference to which particular we are not acting irregularly, if from the books, though not Canonical, yet brought out for the edification of the Church, we bring forward testimony. Thus Eleazar in the battle smote and brought down an elephant, but fell under the very beast that he killed (1 Macc. 6.46).”

John Damascene (AD 675-749). He wrote, “It must be known that there are two and twenty books of the Old Testament, according to the alphabet of the Hebrew language.”

Hugh of St. Victor (AD 1133-1141). He wrote, “There are also in the Old Testament certain other books which are indeed read [in the church] but are not inscribed in the body of the text or in the canon of authority: such are the books of Tobit, Judith and the Maccabees, the so-called Wisdom of Solomon and Ecclesiasticus.”

Cardinal Ximenes (AD 1436-1517). Pope Leo X approved Cardinal Ximenes’ Bible called the Complutensian Polyglot (1514-17). In the preface to this Bible, Ximenes wrote that Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, the Maccabees, the additions to Esther and Daniel were not canonical Scriptures. If he had wrote this 30 years later, he would have been anathematized by the RCC.

Cardinal Cajetan (AD 1469-1534). At the end of his Commentary on all the Authentic Historical Books of the Old Testament (AD 1532), Cardinal Cajetan wrote, “Here we close our commentaries on the historical books of the Old Testament. For the rest (that is, Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees) are counted by St Jerome out of the canonical books, and are placed amongst the Apocrypha, along with Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus, as is plain from the Prologus Galeatus. Nor be thou disturbed, like a raw scholar, if thou shouldest find anywhere, either in the sacred councils or the sacred doctors, these books reckoned as canonical. For the words as well of councils as of doctors are to be reduced to the correction of Jerome. Now, according to his judgment, in the epistle to the bishops Chromatius and Heliodorus, these books (and any other like books in the canon of the bible) are not canonical, that is, not in the nature of a rule for confirming matters of faith. Yet, they may be called canonical, that is, in the nature of a rule for the edification of the faithful, as being received and authorized in the canon of the bible for that purpose. By the help of this distinction thou mayest see thy way clearly through that which Augustine says, and what is written in the provincial council of Carthage.” If Cardinal Cajetan had written these words only 15 years later, he would’ve been anathematized by the RCC.

Not until the Council of Trent (AD 1545-1563) was the Apocrypha declared to be Scripture by the RCC. Geisler and Nix explain,

The action of the Council of Trent was both polemical and prejudicial. In debates with Luther, the Roman Catholics had quoted the Maccabees in support of prayer for the dead (see 2 Mac 12:45-46). Luther and Protestants following him challenged the canonicity of that book, citing the New Testament, the early church Fathers, and Jewish teachers for support. The Council of Trent responded to Luther by canonizing the Apocrypha. Not only is the action of Trent obviously polemical, but it was also prejudicial, since not all of the fourteen (fifteen) books of the Apocrypha were accepted by Trent.

Can we really believe that believers in Christ did not know their own Scriptures for fifteen hundred years of Church History?

In addition to biblical and historical evidences, we should also reject these books on rational grounds.

(Tobit 6:7-9) “Then the young man questioned the angel and said to him, ‘Brother Azariah, what medicinal value is there in the fish’s heart and liver, and in the gall?’ He replied, ‘As for the fish’s heart and liver, you must burn them to make a smoke in the presence of a man or woman afflicted by a demon or evil spirit, and every affliction will flee away and never remain with that person any longer. And as for the gall, anoint a person’s eyes where white films have appeared on them; blow upon them, upon the white films, and the eyes will be healed.’”

Magic incantations are completely absent from the OT. Harvard scholar G. Earnest Wright explains, “The whole pagan world of magic and divination is simply incompatible with the worship of Yahweh… The surprising thing is not that the cult of magic and divination was known in Israel, but that it should be so definitely forbidden in the law and associated by the prophets with an idolatry which destroyed rather than saved.” And yet, the Apocrypha contain magic incantations. Regarding this account, Bruce Metzger writes, “The story is entirely unhistorical.” He continues, “The book of Tobit reflects… the admixture of many speculations derived from folklore and magic (for example, the view that a demon can be exorcized by means of a disagreeable odor).”

(2 Maccabees 12:46) “It is therefore a holy and wholesome thought to pray for the dead, that they may be loosed from sins.”

This concept of prayer for the dead fits with the medieval Roman Catholic teaching of purgatory, but it is not found anywhere in Scripture (see “Purgatory”).

“Your all-powerful hand, which created the world out of formless matter” (Wisdom of Solomon 11:17).

Metzger writes, “The writer describes him as having ‘created the world out of formless matter’ (11:17), adopting here the very phrase which Platonists used to describe the pre-existent matter out of which the world was made, and implying that this unformed matter was itself uncreated.”

“A perishable body weighs down the soul, and this earthy tent burdens the thoughtful mind” (Wisdom of Solomon 9:15).

It also refers to the “imprisoned soul” (16:14). Metzger writes, “As for man, his body is regarded as a mere weight and clog to the soul (9:15), a view which is foreign to both Old Testament and New alike.”

Belief in the preexistence of souls. The Wisdom of Solomon states, “As a child I was naturally gifted, and a good soul fell to my lot; or rather, being good, I entered an undefiled body” (8:19-20).

“For almsgiving saves from death and purges away every sin. Those who give alms will enjoy a full life, but those who commit sin and do wrong are their own worst enemies” (Tobit 12:9-10).

The concept of salvation by works is explicitly taught against in both the Old and New Testaments (see “Do Good People Go To Heaven?”).

Tobit’s lifespan. Tobit claims to have been alive from the Assyrian conquer (722 BC) to the time of Jeroboam’s revolt (931 BC). Yet Tobit 14:11 (cf. 1:3-5) states that his entire lifespan was only 158 years. Tobit is called “a young man” (Tob. 1:4) when the northern tribes split from the kingdom (922 BC), but he is still alive during the deportation (740-731 BC). This would mean that he was alive for at least 182 years! Yet Tobit 14:2 states, “Tobit died in peace when he was one hundred twelve years old.”

Historical problems in Judith. Scholars have long pointed out the historical problems with the book of Judith. Metzger writes, “The consensus, at least among Protestant and Jewish scholars, is that the story is sheer fiction… The book teems with chronological, historical, and geographical improbabilities and downright errors.” DeSilva notes that the proponents of the book “have to face the many historical and geographical errors of the book.” He adds, “The work is better read as a piece of historical fiction—an attempt to write a nonhistorical story set in the midst of known historical personages and dynamics.”

Exaggerated numbers in Judith. Metzger states that the numbers given throughout the book are greatly exaggerated (1:4, 16; 2:5, 15; 7:2, 17).

Exaggerated rates of travel in Judith. Nebuchadnezzar’s general Holofernes (pronounced holl-OFF-ern-ese) travels his army 300 miles in three days (2:21).

Geographical errors in Judith. DeSilva writes, “Holofernes’ itinerary is also confused: he marches through Put (Libya) and then westward across Mesopotamia. Bethulia is not mentioned outside Judith, and, despite the rather numerous geographical clues given by the author, defies identification. Moreover, Jerusalem stands very much open to invasion, the preferred route being to come around and attack the city from the west. Holofernes has no need to attack from the north, and there is no narrow pass that must be crossed in the north for foreign invaders to gain access to Jerusalem. This is a detail borrowed from the story of the battle of Thermopylae.”

Nebuchadnezzar’s dating, reign, and location in Judith. Judith places Nebuchadnezzar’s reign in Nineveh, instead of Babylon (1:1). Metzger points out that the “author places Nebuchadnezzar’s reign over the Assyrians (in reality he was king of Babylon) at Ninevah (which fell seven years before his accession!) at a time when the Jews had only recently returned from the captivity (actually at this time they were suffering further deportations)!” Nebuchadnezzar never fought Media (1:7) and never captured Ecbatana (1:14).

Rebuilding of the Temple in Judith. The author dates the rebuilding of the Temple about a century too early (4:13).

The existence of the Sanhedrin in Judith. The author pictures the Sanhedrin ruling over Israel (6:6-14; 15:8) which is “compatible only with a post-exilic date several hundred years after the book’s presumed historical setting.”

Historical problems in Baruch. The book claims to be written by Baruch—the friend and secretary of Jeremiah (Jer. 32:12; 36:4; 51:59). But deSilva calls this a “literary fiction.” Metzger writes, “Actually it appears to be a composite work of uneven quality written by two or more authors.”

The date of the book is a mystery. Portions of the book (3:36-4:1) are quite similar to Sirach 24:8, 23. This suggests a date later than 180 BC—though it could be as late as 120 BC. The rest of the book could date anywhere from “the fourth through the second centuries B.C.E.” Metzger states that the book could date as late as the first century AD.

Jeremiah 43:6 places Baruch in Egypt—not Babylon (Baruch 1:1). The book states that the Temple vessels came back to the Jews (1:8-11). Baruch states that the Exile would last seven generations (6:3), but the Bible places it at 70 years.

Historical problems in the additions to Esther. The canonical version of Esther is a coherent story without the additions, but an incoherent story with the additions. DeSilva writes, “Without [the additions], the story is a coherent whole; with them, contradictions are unnecessarily introduced into a formerly consistent narrative.

Historical anachronisms. Esther 11:2-12:6 places Mordecai serving in the court of Artaxerxes, but also as a captive coming from Jerusalem under Nebuchadnezzar (about 112 years earlier).

The death of Haman and his sons. The Hebrew text of Esther states that Haman was hanged on a pole, and his sons were killed in the riots (Esther 7:9-10; 9:6-19). But the non-canonical Esther (16:17-18) states that Haman and his sons were all hanged on the city gate. Moreover, the Hebrew text states Haman and his sons died on the thirteenth of Adar (9:1, 13-14), while the non-canonical additions state they died before Adar (16:17-18).

The date of Mordecai’s discovery of the plot. The canonical Esther places this in the 7th year of Artaxerxes (2:16-21), while the non-canonical Esther places this in the 2nd year of Artaxerxes (11:1).

Haman’s ethnicity. The canonical Esther calls Haman an “Agagite” (3:1). The non-canonical Esther calls Haman “a Macedonian… an alien to the Persian blood, and quite devoid of our kindliness” (16:10).

While the canonical Esther doesn’t mention God, angels, or prayer, the additions to Esther have all three in great abundance.

Historical problems in Maccabees. Several problems confront the believer in the historicity of Maccabees.

Internal contradiction for the date of Antiochus’ death. 1 Maccabees states that his death was after the rededication of the Temple, while 2 Maccabees places it before the rededication of the Temple.

Judas purifying the Temple. 2 Maccabees states that Judas purifies the Temple two years after the altar had been desecrated (2 Macc. 10:3), while 1 Maccabees places this differently (1 Macc. 4:52; 1:54-59).

The first expedition of Lysias. The first expedition of Lysias took place before the death of Antiochus Epiphanes (1 Macc. 4:26-35). Metzger comments, “Lysias was defeated by Judas after the appearance of a horseman, clothed in white and brandishing weapons of gold, who rode at the head of the Jewish forces (chap.11).”

3 Maccabees is “historical romance” or “Greek Romance.” DeSilva writes, “The author was seeking to write not history but an edifying tale loosely anchored in history.” He continues, “The view of the majority of scholars, however, is that 3 Maccabees is largely a piece of historical fiction—well-informed historical fiction when it comes to the details that produce verisimilitude, to be sure, but, as concerns an enforced forced assimilation and persecution of the Jews under Ptolemy IV, not a reliable source.”

Why did Augustine accept the Apocrypha? Roman Catholic theologians point out that Augustine believed in the inspiration of the Apocrypha. But others do not find this the authority of Augustine strong enough to overturn the other church fathers for several reasons

Why did some of the early Church Fathers cite the Apocrypha? Many early Christian leaders cite the Apocrypha as Scripture. However, this evidence carries little weight when examined closely.

Why are the Apocrypha in the Septuagint?

Wasn’t the OT canon determined at the Council of Jamnia in AD 90? In 1871, H.H. Graetz propounded the theory that the Jewish canon closed at Jamnia in AD 90. Since then, critical scholars have claimed that the Hebrew canon was not closed until this time.

These short introductions to the Apocryphal books will give the reader insight to the authorship, date, and key content of each book.

1 Esdras This book dates to sometime between 150 BC and AD 70, and it is written by an anonymous author. It is mostly a copying of the Hebrew Bible (2 Chron. 35:1-36:23, Ezra, Neh. 7:73-8:12). Only two and a half chapters are filled with original material (3:1-5:6). Augustine believed that this novel section might contain a prediction of Jesus (City of God, 18.36), but this claim is without warrant.

2 Esdras This is called by various names: 4 Esdras, Latin Ezra, the Apocalypse of Ezra. It is an “apocalypse” or revelation of the end of history. Its main body (chs. 3-14) date to the end of the first century AD, and this section was written by an anonymous Jewish author. Its introduction and conclusion (chs. 1-2, 15-16) date to the second or third centuries AD, and scholars believe these were written and added by Christian authors.

Tobit This story is set during the days of King Shalmaneser in Ninevah (Assyria). Tobit (the protagonist) flees from the authorities for burying Jewish bodies. Tobit is blinded by the defecation of a bird, and the story explains how Tobit gets healed and Sarah and Tobias (Tobit’s son) become married.

Judith This book was written by an anonymous author. It probably dates to after the Maccabean Revolt in ~165 BC. While fictional, unhistorical, and uninspired, the book of Judith is a very fun and interesting tale about a widower defeating a mighty general of a world empire. Nebuchadnezzar’s general Holofernes tries to invade Israel. Judith—a chaste widow—appears half way through the story to save the nation. The general lusts after Judith, and he tries to seduce her. Judith lies to him, draws him in, and waits for the right opportunity to get him drunk and decapitate him. This leads to Israel defending her land, and overtaking over the invading Assyrian army.

Non-canonical Additions to Esther The biblical book of Esther (see “Introduction to Esther”) has several additional verses in the Apocrypha. The apocryphal version of Esther contains an additional 107 verses to the Hebrew text. Modern translations categorize these verses into six major additions.

The Wisdom of Solomon The author wrote the book in Greek, and probably in Alexandria, Egypt. The book mentions the worship of animals (i.e. zoolatry), which was common in Egypt. The book dates somewhere between 200 BC and AD 100.

Ben Sira (or Ecclesiasticus or the Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach) This is the longest book in the Apocrypha. This book is also named “Ecclesiasticus” from the Latin version (i.e. “The Church Book”). This is the only book in the Apocrypha that names himself: Ben Sira (50:27). He was a scribe by profession (51:23). The book dates somewhere 196 to 175 BC.

Baruch This book is a collection of OT texts. It dates somewhere between 180 BC and 120 BC.

The Letter of Jeremiah The author was writing a polemic (or rant) against idolatry.

Additions to Daniel: The Prayer of Azariah, the Song of the Three Men, Susanna, Bel and the Dragon These additions appear in Daniel 3, 13, and 14 in the Latin Vulgate. The anonymous authors wrote the books sometime in the second century BC.

The Prayer of Manasseh This book dates somewhere between 200 BC and AD 50. It contains the supposed prayer of the worst king in Israel’s history: king Manasseh.

Psalm 151 This psalm was written somewhere between the sixth century BC and AD 70.

1 Maccabees This book is considered excellent history of the Maccabean Revolt, where the Jewish elder Mattathias led a revolt against Antiochus Epiphanes IV. The book dates to ~100 BC.

2 Maccabees While 1 Maccabees is a book credited as a good and reliable historical account, 2 Maccabees is not. It dates to ~124 BC. The author bases his theology of history on the blessings and cursings of Deuteronomy 28-30. He sees that the righteous are punished for the sins of the nation, but the righteousness of the few bring the blessings for the whole nation. The book covers the martyrdom of many Jewish people during the reign of Antiochus Epiphanes IV.

3 Maccabees This book covers the events 50 years before the Maccabean Revolt. It takes place in Egypt—not Israel. The literary purpose of this book is to show that God delivers faithful people in the Diaspora, even though they’re away from the Temple. The book could date as earlier as 217 BC, or as late as AD 70. We’re simply not sure. It is not a reliable historical text, being written in the genre of “historical fiction” or “Greek Romance.”

4 Maccabees This book is also written by an unknown author. It dates somewhere in the first half of the first century AD, or maybe later.

Beckwith, Roger. The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism. Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986.

Beckwith is probably the most scholarly resource in print defending a Protestant view of the canon. Beckwith was a Protestant, Anglican scholar (p.6).

Geisler, Norman & Nix, William. A General Introduction to the Bible: Revised and Expanded. Chicago, IL. Moody Press. 1986.

See Chapter 14 (“Development and History of the Old Testament Canon”) and 15 (“The Old Testament Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha”).

Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995.

See Chapter 9 (“The Extent of the Old Testament Canon”).

Metzger, Bruce. An Introduction to the Apocrypha. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Evans, Craig. Noncanonical Writings and New Testament Interpretation. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1992. “Chapter One: The Old Testament Apocrypha.”

DeSilva, David. Introducing the Apocrypha. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002. See also Dr. David deSilva’s nine lectures on the Apocrypha, which can be found here.

David deSilva is professor of NT and Greek at Ashland Theological Seminary, and he is an elder at the United Methodist Church. While his book is a fine introduction to the Apocrypha, we disagree over his views of inerrancy. For instance, he holds that the book of Daniel contains the “historical error of thinking Belshazzar to be Nebuchadnezzar’s son (Dan. 5:2, 11, 13, 18, 22; Bar. 1:11)” (p.203). He dates the book of Daniel to 164 BC (p.203), and he also believes in second and third Isaiah (p.204).

Geisler, Norman & Nix, William. A General Introduction to the Bible: Revised and Expanded. Chicago, IL. Moody Press. 1986. 271.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 377.

Emphasis mine. Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995. 141.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 235-240.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 384. See the books Philo quotes from on p.75 of Beckwith.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), Kindle Locations 368-369.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 277.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 277.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 277.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 381.

Harris writes, “There are more than 600 allusions and about 250 strict quotations. He lists no strict quotations in the books of Judges-Ruth, Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah, Esther, Esslesiastes, Song of Solomon, and Lamentations. Also there are none from Obadiah, Nahum and Zephaniah, but these books were counted as part of the “Book of the Twelve,” the Minor Prophets, which is quoted many times.” Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995. 316.

Armstrong, Dave. A Biblical Defense of Catholicism. Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute, 2003. 262.

Melito’s letter to Onesimus is preserved in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 4.26.7.

However, Harris notes that his list was preserved by Eusebius, which only contains 21. See end note on p. 310. Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995. 131.

Gregg Allison, Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 48.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 395.

E. Earle Ellis, The Old Testament in Early Christianity (Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1991), 19.

Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures 4, 33-36. Cited in E. Earle Ellis, The Old Testament in Early Christianity (Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1991), 20.

Hilary of Poitiers, Commentary in Psalms (Preface 15). E. Earle Ellis, The Old Testament in Early Christianity (Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1991), 26.

Gregg Allison, Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 48.

E. Earle Ellis, The Old Testament in Early Christianity (Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1991), 26. See Epiphanius, Decretum Gelasianum 2.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 252.

Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church and Its Background in Early Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 1986), 253.

Rufinus, Exposito Symboli 35f. Cited in E. Earle Ellis, The Old Testament in Early Christianity (Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1991), 7.

Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995. 130.

Jerome, Preface to the Books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs, NPNF2, 6: 492.

Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995. 187.

Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Scriptures. Greenville, SC, 1995. 187.

Library of the Fathers of the Holy Catholic Church, Gregory the Great, Morals on the Book of Job, vol. II, Parts III and IV, Book XIX. 34 (Oxford: Parker, 1845), p. 424.

John Damascene, Lib. IV. c.18. Cited in William Whitaker, A Disputation on Holy Scripture (Cambridge University Press, 1849), p.64.

Hugh of St. Victor, On the Sacraments, I, Prologue, 7.

Cardinal Cajetan, Commentary on all the Authentic Historical Books of the Old Testament. Cited in William Whitaker, A Disputation on Holy Scripture (Cambridge University Press, 1849), p.48.

Geisler, Norman L., and William E. Nix. From God to Us: How We Got Our Bible. Chicago: Moody, 1974. 97-98.

Wright, G. Ernest. The Old Testament against Its Environment. Chicago: H. Regnery, 1950. 86-87.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 37.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 38.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 73-73.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 74.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 69.

Emphasis mine. Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 50.

Emphasis mine. David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 93.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 50.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 93.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 51.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 51.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 51.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 203.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 204.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 205.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 89.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 110-111.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 115.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 251.

Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 144.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 310.

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 314.

James earned a Master’s degree in Theological Studies from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, graduating magna cum laude. He is the founder of Evidence Unseen and the author of several books. James enjoys serving as a pastor at Dwell Community Church in Columbus, Ohio, where he lives with his wife and their two sons.