Hitchens, Christopher. God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. New York: Twelve, 2007. 114.

Jesus of Nazareth has had more of an impact on world history than any other man to have walked the face of the Earth. In their 2013 book Who’s Bigger? Where Historical Figures Really Rank (published by Cambridge University Press) Steven Skiena and Charles B. Ward place Jesus of Nazareth as the most significant figure in all of human history.

And rightly so. Two thousand years later, this penniless preacher has turned the world upside down.

So it might surprise you to even question whether or not Jesus of Nazareth existed—yet some skeptics are seriously making this claim. For instance, Christopher Hitchens wrote of the “highly questionable existence of Jesus.” Bertrand Russell wrote, “Historically it is quite doubtful whether Christ ever existed at all, and if he did we know nothing about him.” Following in their footsteps, many atheistic websites hold to mythicism—the notion that Jesus was merely a myth created by the early church.

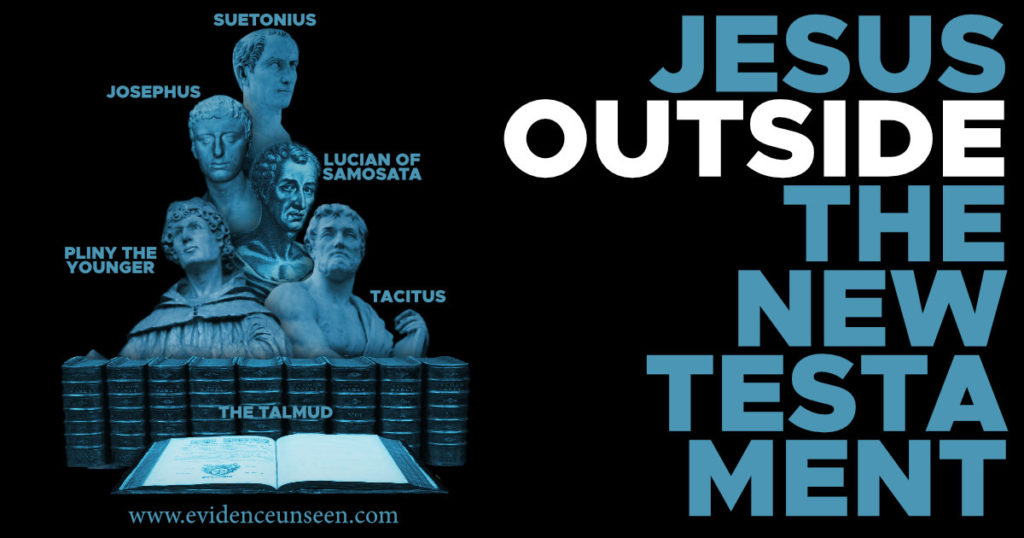

What is the evidence for the existence of Jesus of Nazareth? Was the world changed by a man or by a myth? While a full and robust case can be made by appealing to the New Testament (NT) documents (see Evidence Unseen “Part Four,” 2013), here we will only appeal to the hostile witnesses of history from outside of the NT.

Cornelius Tacitus (AD 55-117) serves as one of the better historical sources from the ancient world. In fact Van Voorst states that Tacitus is “generally considered the greatest Roman historian.” In book 15 and chapter 44 of his Annals, he recounts Emperor Nero’s persecution of Christians in Rome (AD 64).

“Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city as of hatred against mankind. [10] Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination when daylight had expired. Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good but rather to glut the cruelty of one man that they were being destroyed.”

Could this be a Christian interpolation or forgery? Van Voorst states that “the vast majority of scholars [agree] that this passage is fundamentally sound.” He gives four reasons why: (1) the style is the same as the rest of Tacitus’ writing; (2) it fits with the burning of Rome mentioned earlier in the chapter; (3) a Christian interpolator wouldn’t have been so negative toward Christians (“hated for their abominations” “mischievous superstition” “hideous and shameful” “hatred against mankind”); (4) a Christian interpolator wouldn’t have been so terse and succinct in describing Christ. Habermas and Licona concur, “Most scholars accept this passage in Tacitus as authentic,” and even critical scholar John Meier writes, “Despite some feeble attempts to show that this text is a Christian interpolation in Tacitus, the passage is obviously genuine. Not only is it witnessed in all the manuscripts of the Annals, the very anti-Christian tone of the text makes Christian origin almost impossible.”

Why does Tacitus call him Christ? Why not call him Jesus? In the context of chapter 44, Tacitus was trying to explain where “Christians” came from. It makes more sense for him to call their founder “Christ,” rather than “Jesus.” Moreover, at this stage in history, Jesus’ personal name was largely replaced by his title, Christ.

Why does Tacitus call Pilate “procurator” instead of “prefect”? Most scholars believe that the NT title (“prefect”) was correct, and Tacitus had this title wrong. Van Voorst writes, “Most scholars believe that Tacitus’ use of ‘procurator’ was anachronistic, because this title changed from prefect to procurator after AD 41.”

What does this tell us about Jesus? (1) Christians took their name from their founder: Christ (c.f. Acts 11:26). (2) Jesus died under the reign of Pontius Pilate (AD 26-36), and Emperor Tiberius (AD 14-37), which concurs with the NT (Lk. 3:1). (3) Tacitus’ reference to the “extreme penalty” is surely an allusion to crucifixion. The Romans considered crucifixion to be the most shameful death imaginable. (4) An “immense multitude” of Christians had sprung up in Rome by AD 64—even under intense persecution.

Archaeology later vindicated Pontius Pilate. Archaeologist James Hoffmeier writes, “In 1961 a partial inscription bearing his name was discovered there [Palestine] which reads: PONTIUS PILATUS PREFECTUS IUDAEAE, ‘Pontius Pilate, Prefect [governor] of Judea.” This inscription dates to AD 31.

Pliny the Younger (AD 62-113) served as the Roman governor of Bithynia, and he corresponded with his friend Tacitus in his letters. In his 10th book and 96th letter (AD 110), he wrote to the Roman Emperor Trajan, questioning him on how to handle the burgeoning Christian population.

“The whole of their guilt, or their error, was, that they were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ, as to a god, and bound themselves by a solemn oath, not to any wicked deeds, but never to commit any fraud, theft, or adultery, never to falsify their word, nor deny a trust when they should be called upon to deliver it up; after which it was their custom to separate, and then reassemble to partake of food but food of an ordinary and innocent kind. Even this practice, however, they had abandoned after the publication of my edict, by which, according to your orders, I had forbidden political associations. I judged it so much the more necessary to extract the real truth, with the assistance of torture, from two female slaves, who were styled deaconesses: but I could discover nothing more than depraved and excessive superstition. I therefore adjourned the proceedings, and betook myself at once to your counsel. For the matter seemed to me well worth referring to you, especially considering the numbers endangered. Persons of all ranks and ages, and of both sexes are, and will be, involved in the prosecution. For this contagious superstition is not confined to the cities only, but has spread through the villages and rural districts; it seems possible, however, to check and cure it.”

Could this be a forgery? Van Voorst writes, “The text of these two letters is well-attested and stable, and their authenticity is not seriously disputed. Their style matches that of the other letters of Book 10, and they were known already by the time of Tertullian (fl. 196–212). Sherwin-White disposes of the few suggestions, none of which have gained credence, that the letters are whole-cloth forgeries or have key parts interpolated.” Moreover, a Christian forger wouldn’t call Christianity a “contagious superstition.”

What do we learn about Christianity from this passage? (1) The early Christians met under the cover of darkness. (2) They sang to Christ as if he was still alive. (3) They believed Jesus was God. (4) Even enemies of Christianity viewed them as morally distinct people. (5) They would regularly eat meals together. (6) Rome tortured some of the early Christians for their faith. (7) Christianity reached all classes of society, both sexes, and many territories in the Roman Empire (Gal. 3:28).

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillas (AD 69-160) wrote under the Roman emperor Hadrian, and he was a friend of Pliny the Younger.

Because the Jews at Rome caused continuous disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he [Emperor Claudius] expelled them from the city.

Could this be a forgery? This isn’t likely because elsewhere Suetonius refers to Christianity as “a sect professing a new and mischievous religious belief.” Moreover, it isn’t likely that a Christian interpolator would misspell Christ’s name as “Chrestus.” Van Voorst writes, “We conclude with the overwhelming majority of modern scholarship that this sentence is genuine.”

Why does Suetonius call him “Chrestus” instead of “Christ”? The Latin spelling of “Christ” (Christus) is only one letter away from “Chrestus.” Most historians believe that this spelling variation was a common mistake to refer to Christ. Van Voorst writes of the “near-unanimous identification of him with Christ.” A.N. Wilson states, “Only the most perverse scholars have doubted that ‘Chrestus’ is Christ.” Even critic Bart Ehrman explains that “this kind of spelling mistake was common.” Van Voorst writes, “They were pronounced so similarly that they were often confused by the uneducated and educated alike, in speech and in writing.” He cites several NT manuscripts and church fathers that substitute “Chrestus” for “Christus.”- By contrast, the name “‘Chrestus’ does not appear among the hundreds of names of Jews known to us from Roman catacomb inscriptions and other sources.” If another historical figure was causing upheaval in Rome, no other historical source mentions him.

What does this passage tell us? (1) A massive population Christians existed in Rome by AD 49 (Rom. 1:8; 1:13; 15:22-24). (2) Christ was such a popular figure that the Jewish population in Rome rioted over him. Van Voorst notes that the Jews were expelled twice from Rome for seeking non-Jewish converts (AD 19 and AD 139).

Flavius Josephus (AD 37-100) was a Jewish Pharisee and military commander who had been captured by the Romans before the fall of the Temple in AD 70. After being taken prisoner, he began working as the court historian for Emperor Vespasian and adopted a Roman name (“Flavius”). He gives us two important references to Christ:

The judges of the Sanhedrin… brought before them a man named James, the brother of Jesus who was called the Christ, and certain others. He accused them of having transgressed the law and delivered them up to be stoned. Those of the inhabitants of the city who were considered the most fair-minded and who were strict in observance of the law were offended at this.

Josephus demonstrates that James was the brother of Jesus (Gal. 1:19), and James went to his death for belief in his brother Jesus. Regarding this first passage, Van Voorst writes, “The overwhelming majority of scholars holds that the words ‘the brother of Jesus called Christ’ are authentic, as is the entire passage in which it is found.” Josephus offers us another earlier passage about Jesus as well.

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man. For he was one who wrought surprising feats… He was (the) Christ… he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him.

Origen (AD 250) wrote that Josephus was not a Christian. Yet in this passage, Josephus openly affirms the basic truths of Christianity. This is so bizarre that both Christian and critical historians believe that a later Christian scribe must have altered what Josephus originally wrote. Both Irenaeus and Tertullian (AD 200) knew of Josephus’ works, but they didn’t cite this passage. Eusebius (a 4th century Christian historian) quoted this passage from Josephus, so it must have been distorted before that time (AD 325).

Hebrew scholar Shlomo Pines showed an Arabic manuscript (from Agapius’s Universal History—a tenth-century Christian work) in 1971 that might remove the distorted portions of Josephus’ work.

At this time there was a wise man who was called Jesus. His conduct was good and (he) was known to be virtuous. And many people from among the Jews and the other nations became his disciples. Pilate condemned him to be crucified and to die. But those who had become his disciples did not abandon his discipleship. They reported that he had appeared to them three days after his crucifixion, and that he was alive; accordingly he was perhaps the Messiah, concerning whom the prophets have recounted wonders.

Because of this manuscript and literary criticism, most scholars (critical or Christian) believe that we can reconstruct the historical core of what Josephus originally wrote before the scribe distorted it.

Bart Ehrman (atheistic NT critic): “It is far more likely that the core of the passage actually does go back to Josephus himself.” He later continues, “There is absolutely nothing to suggest that the pagan Tacitus or the Jewish Josephus acquired their information about Jesus by reading the Gospels.”

Louis Feldman (a professor of Classics and Literature Emeritus at Yeshiva University and leading Josephus scholar) claimed that somewhere between 3:1 or 5:1 hold to a historical core that goes back to Josephus.

Gerd Theissen (critical scholar): “With reference to Jesus, we have the Testimonium Flavianum (18.63-64), the kernel of which probably goes back to Josephus.” Gerd Theissen writes that a revised, neutral version of Josephus is “most probable. Josephus reported on Jesus in as neutral and objective a way as he did on John the Baptist or James the brother of the Lord.”

Craig Evans (NT scholar): “Most today regard the passage as authentic but edited.”

Paul Meier (a Josephus scholar) states that most scholars do not hold that this passage is either completely authentic, nor a complete forgery. Instead, he writes that “a large majority of scholars today, however share the third position… particularly in view of the newly-discovered Agapian text which shows no signs of interpretation.”

John-Dominic Crossan (radical NT scholar): “Even if Christian editors delicately inserted those italicized phrases later to make the description more positive, the basic content of the passage is most likely original.”

There are several reasons why scholars believe that this core of Josephus is original and uncorrupted:

First, the Arabic version gives empirical evidence of a core version. The Arabic version fits with what we know about Josephus’ view of Christianity. This manuscript doesn’t affirm that these events actually happened. Instead, it states that Jesus’ disciples merely “reported” these things.

Second, the language fits with Josephus—not an interpolator. The NT authors never call Jesus a “wise man.” While the expression “amazing deeds” is similar to Luke 5:26, it is nowhere else attested in the NT. Furthermore, the term “tribe” is also “Josephan but not Christian.”

Third, the mention of Jesus in chapter 20 points to an earlier mention of Jesus. Josephus mentioned Jesus briefly in chapter 20, when he says, “Jesus who was called the Christ.” This off-the-cuff remark leads us to believe Josephus already referred to Jesus with this messianic title earlier in his book (in chapter 18).

What does this passage tell us? (1) Jesus was considered a man of virtue and wisdom. (2) Both Jews and Gentiles became his disciples. (3) Pilate sentenced him to death. (4) His disciples followed him after his death. (5) His disciples claimed that he appeared to them alive after three days. (6) Jesus’ disciples also claimed that these events fulfilled Old Testament predictive prophecy.

Lucian of Samosata was a second century Greek satirist (AD 115-200), who was highly critical of Christianity. He wrote The Death of Peregrinus around AD 165. Peregrinus was a (pseudo?) Christian convert who returned to Cynicism and politics, committing suicide on a pyre near the Olympic Games in AD 165. When the authorities placed Peregrinus in jail, the Christians visited him and brought him food. Lucian thinks they were duped by Peregrinus. Van Voorst writes, “Lucian’s point is to warn readers against the kind of life led by Peregrinus, whose emotionality and theatricality were opposed to the reasonable moderation that Lucian advocated.”

The Christians, you know, worship a man to this day—the distinguished personage who introduced their novel rites, and was crucified on that account… You see, these misguided creatures start with the general conviction that they are immortal for all time, which explains the contempt of death and voluntary self-devotion which are so common among them; and then it was impressed on them by their original lawgiver that they are all brothers, from the moment that they are converted, and deny the gods of Greece, and worship the crucified sage, and live after his laws. All this they take quite on faith, with the result that they despise all worldly goods alike, regarding them merely as common property.

Was this a forgery? Lucian was no friend of Christians, calling them “misguided creatures.” Moreover, Lucian’s language is dissimilar to NT language. Van Voorst writes, “The use of the non-New Testament words ‘patron,’ ‘lawgiver,’ and especially his characteristic word for ‘crucified’ also argues tellingly against a New Testament source. So there is no literary or oral connection between Lucian and the New Testament and other early Christian literature in regard to the person of Jesus.”

What can we learn from Lucian? (1) Christians worshiped Jesus after his death. (2) Jesus died by crucifixion. Van Voorst writes, “Lucian’s verb originally meant ‘to impale, fix on a stake,’ but unquestionably refers here to crucifixion. He uses this verb exclusively for crucifixion; it also occurs in his Prometheus 2, 7, and 10, and in Iudiceum vocalium 12.” (3) Christians believed that they had received eternal life, giving them courage over death. (4) They sacrificially served others and visited prisoners (Mt. 25:35; Heb. 13:3; Acts 2:44-45). (5) Christians believed that they were spiritual brothers with one another (Mt. 23:8). (6) Christians denied polytheism and paganism.

Thallus (a Mediterranean historian) wrote sometime in the first century. His writing does not exist, but Julius Africanus (a Christian historian) quoted Thallus in AD 221. Evans writes that “the value of this fragment is slight,” but it shows that someone in the first century knew about the darkness and was trying to refute it.

JULIUS COMMENTING ON AND QUOTING THALLUS: “On the whole world there pressed a most fearful darkness; and the rocks were rent by an earthquake, and many places in Judea and other districts were thrown down. This darkness Thallus, in the third book of his History, calls, as appears to me without reason, an eclipse of the sun.”

Why should we view this as authentic? Julius Africanus doesn’t seem like he is inventing this excerpt from Thallus, but instead he is arguing with Thallus’ claim that an eclipse could’ve caused the darkness. He is arguing that “at full moon a solar eclipse is impossible, and the Passover always falls at full moon.”

Tertullian claimed that this darkness was a “cosmic” or “world event,” which he boasted was known by the Romans. Africanus recorded Phlegon of Tralles (a Greek author from Caria), regarding the “world darkness” in AD 137. Phlegon wrote that in the 202nd Olympiad (AD 33) there was “the greatest eclipse of the sun” and “it became night in the sixth hour of the day [i.e., noon] so that stars even appeared in the heavens. There was a great earthquake in Bithynia, and many things were overturned in Nicaea.”

This passage shows that the message of Christ had reached the Mediterranean by AD 50. Van Voorst places Thallus in the 207th Olympiad (AD 49-52), and states that “most scholars” date him to this time: around AD 50.

Mara Bar-Serapion was a Syrian philosopher, who wrote a letter to his son sometime after AD 73. William Cureton dates the letter to the end of the first century, though most scholars date this letter to the second century, because he refers to the Jews as desolate and scattered, which fits better after the Bar Kokhba Revolt (AD 135). There is only one manuscript of his letter in existence, dating to the 7th century and preserved in the British Museum.

What advantage did the Athenians gain from putting Socrates to death? Famine and plague came upon them as a judgment for their crime. What advantage did the men of Samos gain from burning Pythagoras? In a moment their land was covered with sand. What advantage did the Jews gain from executing their wise King? It was just after that that their kingdom was abolished. God justly avenged these three wise men: the Athenians died of hunger; the Samians were overwhelmed by the sea; the Jews, ruined and driven from their land, live in complete dispersion. But Socrates did not die for good; he lived on in the statue of Hera. Nor did the wise King die for good; he lived on in the teaching which he had given.

Was this a forgery? Craig Evans writes, “Regarding Jesus as the Jew’s ‘wise king,’ instead of the world’s savior or God’s son, suggests that bar Serapion’ impressions were probably formed more by non-Christian sources than by Christian. Indeed, both elements, ‘wise’ and ‘king,’ cohere with the best attested non-Christian witnesses… Further proof that Bar Serapion was not himself a Christian is seen in his statement that Jesus lives on in his teaching, rather than living on in his resurrection.”

What can we learn from this letter? (1) Jesus was called the King of the Jews (Mk. 15:26). (2) He was killed before AD 70 and the destruction of the Temple. (3) God judged the nation of Israel for rejecting Jesus (Mt. 23:37-39, 24:2, 27:25; Mk. 13:1-2; Lk. 19:42-44, 21:5-6, 20-24; 23:28-31). (4) Bar Serapion doesn’t use Jesus’ name or title (Christ). Yet he places him in the category of Socrates and Pythagoras.

The Misnah (the “Tannaitic” literature) dates from the first century to roughly AD 200. The Amoraic period wrote commentaries on the Misnah: one in Palestine and one (larger, more important) in Babylon. This excerpt comes from this later literature.

On the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, “He is going forth to be stoned because he has practiced sorcery and enticed Israel to apostasy. Anyone who can say anything in his favour, let him come forward and plead on his behalf.” But since nothing was brought forward in his favour he was hanged on the eve of the Passover!

How reliable are these rabbinic sources? Craig Evans writes, “[A] serious problem in making use of these traditions is that it is likely that none of it is independent of Christian sources.” Generally scholars do not believe that these excerpts are very historically reliable for several reasons: (1) The rabbis weren’t focused on history—but torah (law). They knew very little about second Temple Judaism, and specifically little about pre-70 Palestine. We don’t have any of their writings from the first or second century. (2) The Misnah—the earlier writings—contain no explicit references to Jesus. (3) The basis for this excerpt in Sanhedrin 43a is most likely “a strong indication that we have here an apologetic response to Christian statements about an unjust trial.”

What can we learn from this excerpt? While this source is limited in its historical value, we can learn a number of details from it: (1) The religious leaders killed Jesus on the day before Passover. (2) The religious leaders were aware of Yeshua (“Jesus”). In another passage, we read, “Jesus the Nazarene practiced magic and led Israel astray.” Van Voorst writes, “That this is Jesus of Nazareth is almost universally agreed.” (3) The religious leaders believed that Jesus was empowered by Satan to perform his miracles (Mt. 12:24). (4) Jesus was “hanged” or crucified (Gal. 3:13; Lk. 23:39). (5) The religious leaders had intent to stone Jesus for blasphemy (Jn. 8:58; 10:31-33; 39). However, he was “hanged” or crucified instead.

Those trained in history and classics haven’t been persuaded by the claims of mythicists. Even skeptics of Christianity believe that Jesus of Nazareth existed.

Maurice Casey (an emeritus professor at the University of Nottingham) “left the Christian faith in 1962” and calls himself “completely irreligious.” Yet regarding mythicism, he writes,

The whole idea that Jesus of Nazareth did not exist as a historical figure is verifiably false. Moreover, it has not been produced by anyone or anything with any reasonable relationship to critical scholarship. It belongs in the fantasy lives of people who used to be fundamentalist Christians. They did not believe in critical scholarship then, and they do not do so now. I cannot find any evidence that any of them have adequate professional qualifications… None of them has proper qualifications in New Testament Studies from a decent university.

It is very striking that the majority of people who write books claiming that Jesus did not exist, and who give their past history are effectively former American fundamentalists.

Unlike published scholarly work, the internet is uncontrolled and apparently uncontrollable, making it a perfect forum for people with negative views about critical scholarship.

Therefore the mythicist view should therefore be regarded as verifiably false from beginning to end.

Bart Ehrman (an atheistic scholar and critic of Christianity) writes,

To dismiss the Gospels from the historical record is neither fair nor scholarly.

None of this literature is written by scholars trained in the New Testament.

The view that Jesus existed is held by virtually every expert on the planet.

Of course, Ehrman and Casey both reject the Christian faith, but they reject the views of mythicism as well.

As we survey the evidence, we discover that mythicism is itself a myth held by a radical fringe in the atheistic subculture. While mythicism fills the pages of skeptical websites, atheistic critics in the scholarly world consider mythicism to be patently false and academically bizarre. Even if we did not appeal to the NT documents or the voluminous writings of the church fathers to learn about Jesus of Nazareth, we could still discover a number of facts about the life of Jesus from the enemies of Christianity. These would include (1) reports about his miracle-working, (2) his crucifixion under Tiberius and Pontius Pilate, (3) reports of his resurrection from the dead, (4) his followers worshiping him as God, and (5) the rapid spread of his message of love and forgiveness across the ancient world. Thus even if we appeal to the hostile witnesses from the past, we discover a clear and concise picture of the historical Jesus.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012.

Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000.

First, Jewish rabbis shouldn’t be expected to have recorded historical accounts about Jesus because they were encountering world-changing turmoil in the first-century. With the Temple being destroyed and the Jewish people be scattered across the world, it’s no wonder that these Jewish rabbis didn’t have time to record historical accounts of Jesus of Nazareth. Van Voorst explains, “They were occupied with a much more pressing matter—preserving the Jewish religion after the devastation of the revolt in 66–70 c.e. and the second revolt in 132–135 c.e. Dealing with traditions about Jesus does not seem to have been an important part of this effort at self-preservation. Also, the rabbis could and did deal with Christians without mentioning their founder.”

Second, the rabbinical strategy was to separate from Christians—not to record details about Christ. Van Voorst writes, “Rabbinic literature was not oriented to history primarily, but to religious law.”

First, Roman historians did not record events like a modern reporter would today. Van Voorst writes, “Historical interpretation of events was not the “instant analysis” we have become accustomed to, for better or worse, in modern times. Most works by major writers, especially self-respecting historians, used recognized literary sources from earlier, lesser writers. The former seem to have been reluctant to be the first to write about relatively recent events. For example, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus, in the introduction to his Jewish War, had to justify writing about ‘events which have not previously been recorded’ (J.W. Preface 5 §15).”

Second, Roman historians would not write about events unless they had a direct effect upon Rome. Why would they record histories of a penniless preacher from Galilee unless he would somehow affect the Roman Empire? Van Voorst writes, “Christianity would not have been treated by Roman writers unless and until it became an important political or social issue for the Romans.” This explains why later second-century historians took more of an interest in Christ, as Christianity spread across the Roman Empire.

Third, most of the manuscripts of the Roman era have been destroyed. Van Voorst writes, “The works of those Roman historians who were contemporary with Jesus, or lived in the next eighty-five years after him, have almost completely perished. Nearly a century of Latin historical writing has vanished, the work of all the writers from Livy (died in 17 c.e.) to Tacitus. The only exception is the inconsistent, panegyrical work of Velleius Paterculus; but since this work extends only to 29 c.e. and likely was written in 30 about events mostly in Rome, we can hardly expect it to mention Jesus.” This is why atheist Bart Ehrman writes, “It is a modern ‘myth’ to say that we have extensive Roman records from antiquity that surely would have mentioned someone like Jesus had he existed.”

Philo of Alexandria (25 BC to AD 50) was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher from Alexandria, Egypt. Skeptics wonder why Philo would not mention Jesus if he was a contemporary of his, and he was also Jewish. There are several answers to this question:

First, Philo wasn’t near Jesus in Israel. He lived in Alexandria, and Jesus travelled in and around Judea. Agnostic historian Maurice Casey writes, “Philo was nowhere near at the time, and had no reason to hear of the events that did happen, let alone report on an increasingly Gentile version of Judaism.”

Second, Philo was more interested in Roman culture—not orthodox Judaism. Philo is best known for his integration of Greek philosophy with Jewish theology. As an Alexandrian, he wouldn’t have networked in Judaism at the time. It’s no wonder that he doesn’t mention Jesus, who was thoroughly Jewish.

Third, Philo doesn’t even mention Christianity or even Christians. No one would argue that Christianity spread throughout the ancient world in the first-century. Yet Philo makes no mention of Christianity at all. Van Voorst notes, “As we stated above, Philo does not mention Jesus. While arguing from silence is always difficult, a plausible explanation for this is that he never mentions Christianity, so he has no need to mention its founder (if he even knew of him at all).”

Hitchens, Christopher. God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. New York: Twelve, 2007. 114.

Russell, Bertrand. Why I Am Not a Christian. London: George Allen and Unwin. 1957. 16.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 39.

Cornelius Tacitus, Annals, 15:44.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 42-43.

Norma Miller writes, “The well-intentioned pagan glossers of ancient texts do not normally express themselves in Tacitean Latin.” Norma P. Miller, Tacitus: Annals XV (London: Macmillan, 1973) xxviii. Cited in Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 43. Van Voorst writes, “Tacitus certainly did not draw, directly or indirectly, on writings that came to form the New Testament. No literary or oral dependence can be demonstrated between his description and the Gospel accounts.” (p.49)

Habermas, Gary R., and Mike Licona. The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2004. 273.

Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Volume 1. New York: Doubleday, 1991. 90.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 48.

Philo, Legation to Gaius 299–305; Josephus, Jewish War 2.9.2–4 §169–77; Antiquities 18.3.1–4.2 §55–64, 85–89.

See Cicero, Against Verres II.v.64. paragraph 165; II.v.66, paragraph 170.

Hoffmeier, James Karl. The Archaeology of the Bible. Oxford: Lion, 2008. 155.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 48.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, 1.7, 6.16.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, 10:96.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 27.

Pliny, Letters 1.18.

Suetonius, Life of Claudius, 25:4.

Suetonius, Life of Nero, Paragraph 16.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 30-31.

Blomberg, Craig. From Pentecost to Patmos: an Introduction to Acts through Revelation. Nashville, TN: B & H Academic, 2006. 234.

For instance, Craig Evans writes, “The variation in spelling was common enough and is even documented in the best of the New Testament manuscripts.” Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. 383. Historian Craig Blomberg writes, “Most historians think that Suetonius’s statement reflects a garbled reference to Christian and non-Christian Jews squabbling over the truth of the gospel.” Blomberg, Craig. From Pentecost to Patmos: an Introduction to Acts through Revelation. Nashville, TN: B & H Academic, 2006. 234-235.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 32.

A. N. Wilson, Paul: The Mind of the Apostle (London: Norton, 1997) 104. Cited in Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 32.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 53.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 34.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 35-36.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 33.

It is also interesting to note how this reference to Claudius’ decree lines up with the biblical account of Priscilla and Aquila—two early Christian leaders. Luke recorded that Priscilla and Aquila were kicked out of Rome in 49 C.E., because of Claudius’ decree (Acts 18:2). However, when Paul writes his letter to the Romans in 56-57 C.E., Priscilla and Aquila were back in their home (Rom. 16:3-5). How did they get back in, if Claudius had kicked all of the Jews out in 49 C.E.? This account makes sense, when we realize that Claudius died in 54 C.E. After his death, the decree was rescinded, and the Jews were allowed back into the city. Priscilla and Aquila arrived just in time for Paul to address his letter to them and the church in their house (Rom. 16:5). This is a small point, which corroborates the biblical account in many ways.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 37.

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 20:197-203.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 83.

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 18:63-64.

Origen was familiar with both the passage about James the Lord’s brother and John the Baptist; however, he is not familiar with this passage. Against Celsus 1.45; Commentary on Matthew 10.17; cf. also Against Celsus 2.13.

Ecclesiastical History, 1.11.

Yamauchi writes that it was copied “by Agapius, the tenth-century Melkite bishop of Hierapolis in Syria… All these differences lead Pines to conclude that the Arabic version may preserve a text that is close to the original, untampered text of Josephus.” Wilkins, Michael J., and James Porter Moreland. Jesus under Fire. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995. 212.

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 20:197-203.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 64.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 97.

Obtained in a private email with the authors, Habermas and Licona. Habermas, Gary R., and Mike Licona. The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2004. 268-269.

Theissen, Gerd, and Dagmar Winter. The Quest for the Plausible Jesus: The Question of Criteria. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2002. 14.

Theissen, Gerd, and Annette Merz. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998. 74.

Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. 390.

Meier, Paul. Josephus: The Essential Works. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1994. 284.

Crossan, John Dominic. The Birth of Christianity. New York, NY: Harper Collins. 1998. 12.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 102.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 58-59.

Lucian, The Death of Peregrine, 11-13.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 64.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 63.

Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. 381.

Julius Africanus, History of the World.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 20.

Tertullian writes to the Roman governors, “You yourselves have the account of the world-portent still in your archives.” Tertullian Apologeticus Chapter 21:19. These were lost, but this passage shows that they were known to the Romans at the time.

Maier, Paul L. Pontius Pilate,. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968. Footnote. Cited in Strobel, Lee. The Case for Christ: a Journalist’s Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1998. 85.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 22.

Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. 382.

Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. 382-383.

Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 43a.

Evans, Craig. The Historical Jesus: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Volume 4. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 2004. 376.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 104-105.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 107.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 118.

b. Sanhedrin 107b; cf. b. Sotah 47a. Cited in Wilkins, Michael J., and James Porter Moreland. Jesus under Fire. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995. 212.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 118.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 3.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 39.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 243.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 2.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 2.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 245.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 73.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 2.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 4.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 129-130.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 130.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 70.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 70.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 70.

Ehrman, Bart D. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne, 2012. 45.

Casey, Maurice. Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 14.

Van Voorst, Robert. Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2000. 131.

James earned a Master’s degree in Theological Studies from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, graduating magna cum laude. He is the founder of Evidence Unseen and the author of several books. James enjoys serving as a pastor at Dwell Community Church in Columbus, Ohio, where he lives with his wife and their two sons.