The Trinity is not merely some dry doctrinal affirmation studied by scholars. It is truly at the heart of the Christian faith. It gives us intellectual, existential, sociological, and devotional insights that change our lives.

The Trinity is not merely some dry doctrinal affirmation studied by scholars. It is truly at the heart of the Christian faith. It gives us intellectual, existential, sociological, and devotional insights that change our lives.

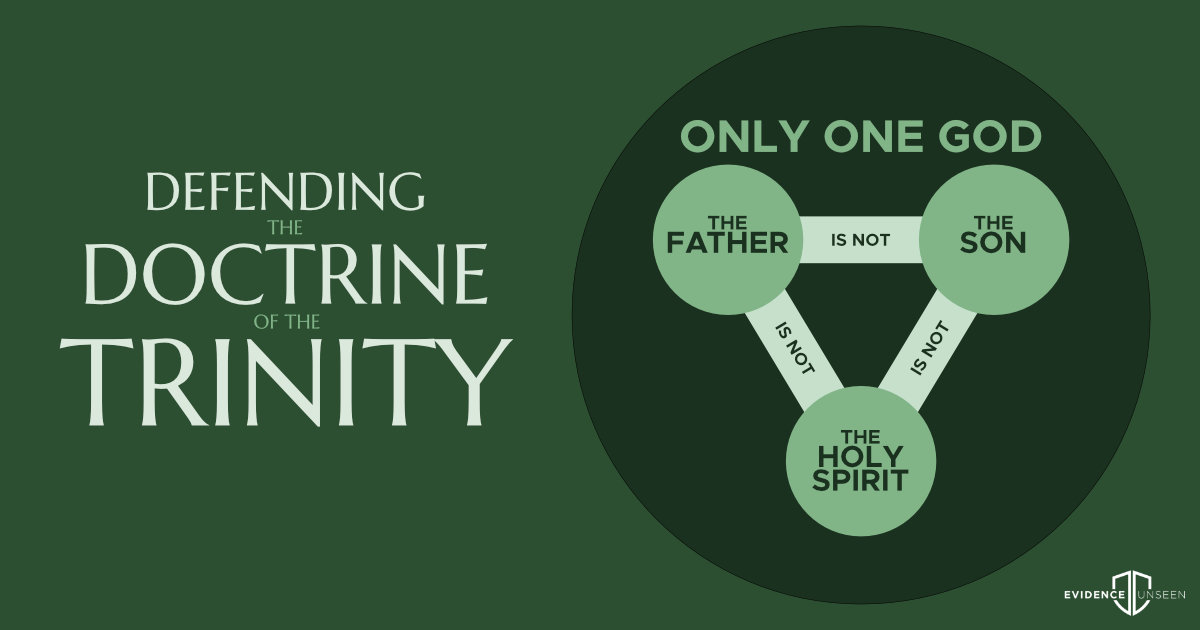

First, the doctrine of the Trinity resolves the three propositions listed above. By way of review, we saw that the Bible teaches these three propositions:

- There is only ONE GOD

- The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all DISTINCT PERSONS

- The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all TRULY GOD

The doctrine of the Trinity beautifully resolves these propositions. This is why we would say that the Trinity is not a problem, but a solution for the biblical data. For those who deny the Trinity, how can we better explain these three propositions of Scripture? Unitarians have a “lot of explaining to do.” Indeed, “if the theologian and exegete are to avoid a contradiction, the traditional formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity seems required.”[1]

Second, the doctrine of the Trinity resolves the tension between God’s love and his self-existence.[2] Love needs a lover and a beloved. It needs a giver and a receiver. But this raises a key problem for the Unitarian: How could God be eternally loving and personal without having relationships?

The Trinity beautifully explains how God can be eternally loving, but not solitary or lonely. Love always existed within God because the persons of the Trinity always gave and received love (Jn. 17:5, 24; Eph. 1:4). Without multiple persons in his eternal nature, God would need humans to express love. This aspect of God’s self-existence remains unresolved in Unitarian monotheisms like Judaism, Islam, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Reeves’ comments are quite insightful and worth quoting at length:

Allah is said to have ninety-nine names, titles which describe him as he is in himself in eternity. One of them is ‘The Loving.’ But how could Allah be loving in eternity? Before he created there was nothing else in existence that he could love (and the title does not refer to self-centered love but love for others). The only option is that Allah eternally loves his creation. But that in itself raises an enormous problem: if Allah needs his creation to be who he is in himself (‘loving’), then Allah is dependent on his own creation, and one of the cardinal beliefs of Islam is that Allah is dependent on nothing.[3]

Single-person gods, having spent eternity alone, are inevitably self-centered beings, and so it becomes hard to see why they would ever cause anything else to exist. Wouldn’t the existence of a universe be an irritating distraction for the god whose greatest pleasure is looking in a mirror? Creating just looks like a deeply unnatural thing for such a god to do. And if such gods do create, they always seem to do so out of an essential neediness or desire to use what they create merely for their own self-gratification.[4]

Allah is a single-person God who has an eternal word beside him in heaven, the Qur’an. At a glance, that seems to make Allah look less eternally lonely. But what is so significant is the fact that Allah’s word is a book, not a true companion for him. And it is a book that is only about him. Thus when Allah gives us his Qur’an, he gives us some thing, a deposit of information about himself and how he likes things. However, when the triune God gives us his Word, he gives us his very self, for the Son is the Word of God, the perfect revelation of his Father. The Word was with God and the Word was God. It is all, well, very revealing. This God does not give us some thing that is other than himself, or merely tell us about himself; he actually gives us himself. If he just dropped a book from heaven, he could keep us at the sort of distance we would expect. But he doesn’t. The very Word of God who is God comes to us and dwells with us.[5]

Just study comparative religions to see the significance of this claim. The great goddess Artemis needed her worshippers (Acts 19:27-28). Her security is symbiotic and parasitic with her worshippers (Acts 19:27-28).[6] Likewise, the Mesopotamian myths depict humans as divine slaves. According to the Enuma Elish, “Man’s purpose in life was to be the service of the gods.”[7] The gods needed humans. However, the Trinity teaches that God needs nothing from us. He only wants to give.

Third, the doctrine of the Trinity shows the depths of God’s love for us. God the Father loves his Son with an infinite and eternal love. Referring to Jesus, God says, “[He is] My chosen one in whom My soul delights” (Isa. 42:1). Elsewhere, God the Father send his Spirit to Jesus “descending like a dove and coming to rest on him.” And then, the Father spoke the powerful words, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” (Mt. 3:16-17 ESV). Reeves writes,

When the Spirit rested upon the Son at his baptism, Jesus heard the Father declare from heaven: ‘You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.’ But now that the same Spirit of sonship rests on me, the same words apply to me: in Christ my high priest I am an adopted, beloved, Spirit-anointed son. As Jesus says to the Father in John 17:23, you ‘have loved them even as you have loved me.’ And so, as the Son brings me before his Father, with their Spirit in me I can boldly cry, ‘Abba,’ for their fellowship I now freely share: the Most High my Father, the Son my great brother, the Spirit no longer Jesus’ Comforter alone, but mine.[8]

God the Father “delights” in the Son, and he is “well pleased” with the Son. And what is the ultimate gift that the Father can give to his Son? What do you give to the God who has everything? The Holy Spirit. At his baptism, the Father loved his Son through the gift of the Holy Spirit descending on him.

The Holy Spirit is the ultimate gift. Otherwise, the Father would’ve given something greater to the Son. This hits home for us when we realize that this is the gift God chose to give us as his adopted children: He gave us the ultimate gift of the Holy Spirit. This is why Jesus could pray to the Father, “[You] loved them, even as You have loved Me” (Jn. 17:23). Reeves writes, “The way the Father makes known his love is precisely through giving his Spirit. In Romans 5:5, for instance, Paul writes of how God pours his love into our hearts by the Holy Spirit. It is, then, through giving him the Spirit that the Father declares his love for the Son.”[9]

Fourth, the doctrine of the Trinity provides a basis for personal love relationships. Human love relationships are not the result of the herd-mentality or some sort of biological accident. Love relationships reflect the very nature of God, because God is a community of love relationships. This explains why love relationships give us the most meaning to life. It also explains why punishments like solitary confinement are one of the worst punishments we can administer in our justice system: We weren’t designed to live in isolation from other personal beings.

Fifth, the doctrine of the Trinity explains why God would value diversity. The Trinity explains why we are unified as a family (Eph. 2:15-18). It explains why God values diversity. This is because he is diverse. Again, Reeves is particularly insightful:

Oneness for the single-person God would mean sameness. Alone for eternity without any beside him, why would he value others and their differences? Think how it works out for Allah: under his influence, the once-diverse cultures of Nigeria, Persia and Indonesia are made, deliberately and increasingly, the same. Islam presents a complete way of life for individuals, nations and cultures, binding them into one way of praying, one way of marrying, buying, fighting, relating—even, some would say, one way of eating and dressing. Oneness for the triune God means unity. As the Father is absolutely one with his Son, and yet is not his Son, so Jesus prays that believers might be one, but not that they might all be the same. Created male and female, in the image of this God, and with many other good differences between us, we come together valuing the way the triune God has made us each unique.[10]

Is it surprising that Islamic nations are associated with monolithic and dictatorial political systems?[11]

Sixth, the doctrine of the Trinity makes the incarnation and atonement possible. Without three separate persons, the Father would not be able to pour judgment out on the Son, and the Son would not have been able to offer himself as a sacrifice for our sin. Our doctrine of God will necessarily affect our doctrine of salvation; the two hang and fall together. Thus, we see that the doctrine of the Trinity is not merely an abstract theological concept. Instead, it lies at the heart of the Christian faith.

Seventh, the doctrine of the Trinity makes the atonement just. Without the Trinity, God would be taking out his wrath on an innocent human being. With the doctrine of the Trinity, God took his wrath out on himself. As Erickson writes, “The truth would be better served by seeing that the judge himself steps down from the bench, removes his robes, and proposes to serve the sentence himself.”[12] But if there is no Trinity, then the Cosmic Judge didn’t pay for human sin. Rather, he redirected the punishment to someone else in the courtroom (the bailiff or the stenographer perhaps!).

Without the Trinity, God stood far away from the Cross, effectively telling Jesus, “You go and suffer and die. I’ll hang back and watch.” With the Trinity, Jesus voluntarily paid for human sin. God himself hung naked from a Roman Cross. In the Trinity, we see submission and humility as being central to the very character of God himself.

[1] John Feinberg, No One Like Him: The Doctrine of God (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2001), 443.

[2] Francis A. Schaeffer, Genesis in Space and Time (Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity, 1972), 26.

J.P. Moreland and William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview (2nd ed., Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017), 1211-1212.

[3] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 40.

[4] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 41.

[5] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 80.

[6] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 46.

[7] Alexander Heidel, The Babylonian Genesis: the Story of Creation (2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1963), p.120.

[8] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 75.

[9] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 29.

[10] Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 103.

[11] L. Berkhof, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans publishing co., 1938), 89.

[12] Millard J. Erickson, Making Sense of the Trinity, 3 Crucial Questions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2000), 75.